I begin this new creative series with a shameful confession. Despite being a reader of epic proportions and book hoarder with stocks ready to rival the local lending library – I have never read Hemingway.

I know of his influence, his stature within the pantheon of literary greats and I know of his issuance of numerous examples of the finest in literature and journalism, but I have never delved within the pages of any of his works – at all – to explore and understand his credentials as being one of history’s greatest writers. I’m at a loss as to how I can even explain this omission. Perhaps it’s as simple as it was not part of the curriculum of classic literature that was ground through my head as a school pupil – where we were forced to analyse to the point of tedium. Perhaps the apparent monolithic slabs of novels proved overwhelming. Even the very male subject matter of the titles? I don’t really know that I can say.

I stumbled across Hemingway and his potential relevance to me on Facebook. I clicked on a link to a brainpickings article by Maria Popova, which centred on an anthology of Hemingway’s quotes on the writers craft – Hemingway on Writing – compiled by Larry W Phillips. It piqued my interest in the world of a person who had, until then, been an anonymous name on a bookshelf. The article included a quote – the most important portion of the quote, indeed the most significant to me, was: “Listen now. When people talk listen completely. Don’t be thinking what you’re going to say. Most people never listen.” This quote resonated with me, Hemingway’s hook that caught me. Not because perhaps I always listen to people in this way – but that I always feel the need to listen to understand.

I cannot read people well – body language is an area I find difficult to read. I don’t analyse on the basis of people’s possible motives, the commonly understood social signifiers of the internal thought processes. I have to garner my understanding from what they say to me, taking note so I can fact check so I can compare the verbal data they convey to me against known facts and other information sources. Over the years I have started to pick up the inherent meanings of some commonly used pieces of indicative non-verbal communication, but it remains difficult, I still can’t spot a liar. So I have to watch and listen to comprehend meaning. A friend once told me that he appreciated the fact that I listened to understand, rather than to answer. Hemingway goes onto say is, this being crucial, that process of observation is the key to the understanding and articulating of the human experience, and to be able to pinpoint the links between your own emotional experience and what you observe.

The resonance was clear and bell like – Hemingway’s words rang clearly in me. This was a truth I could relate to; it was as if it was part of my truth. The article triggered the interest me. I explored more about Hemingway, purchasing the book and gorging on its contents. Hemingway’s voice was clear, with its neat terminology, its warm observance of his truth and his advice suggestive of frustration, of struggle and the wrenching nature of the artistic experience.

Like Hemingway I had once been a journalist. I’d been moulded and instructed in the black art of reducing events to the most condensed form of communication – where succinct sentences would be constructed to paint pen pictures accessible even to the most uneducated reader. It was in the newsroom of several fine local papers, during the last hurrah of the local weekly and evening newspapers, this child of the 1980/90s English education system had sat beside frustrated news editors and sub editors to actually learn the basics of punctuation and grammar – with these respected journalists flinching at my superfluous words and nonsensical grammar.

Throughout this time (5 years all told) I’d hoped, perhaps even assumed, a novel was in me. That it was just something that would come easily and be a consequence of being a writer. But the effort and patience which was clearly needed always eluded me. I’d been unable to bring forth any complete work. Alongside my mammoth collection of other people’s books is a proliferate collection of notebooks with semi-articulated thought processes, scraps of paper with snippets of prose – thoughts that popped into my head and bothered me sufficiently to commit it to paper before my mind has moved onto other matters temporal. Among the abused stationery are portions of stories, where embryonic thought processes have half hatched before being abandoned. It seems I’ve always felt the need to write and, even in the face of repeated failure to finish any work, it seems the urge is unlikely to go away.

So within the pages of Phillips’ collection I hungrily devoured the wisdom of a man who I had thus far been able to ignore. His words seemed, to me, to carry instructional weight, suggestive of method. His words appealed to me in a way that left me motivated – perhaps to learn more about the man, his ways and thought and inspiration to hone the craft.

“I was trying to write and then I found the greatest difficulty, aside from knowing truly what you realy felt, rather than what you were supposed to feel, and had been taught to feel, was to put down what really happened in action; what the actual things were which produced the emotion that you experienced. In writing for a newspaper you told what happened and, with one trick and another, you communicated the emotion aided by the element of timeliness which gives a certain emotion to any account of something that has happened on that day; but the real thing, the sequence of motion and fact which made the emotion and which would be as valid in a year or in ten years or, with luck and if you stated it purely enough, always, was beyond me and I was working very hard to get it.”

Death in the Afternoon

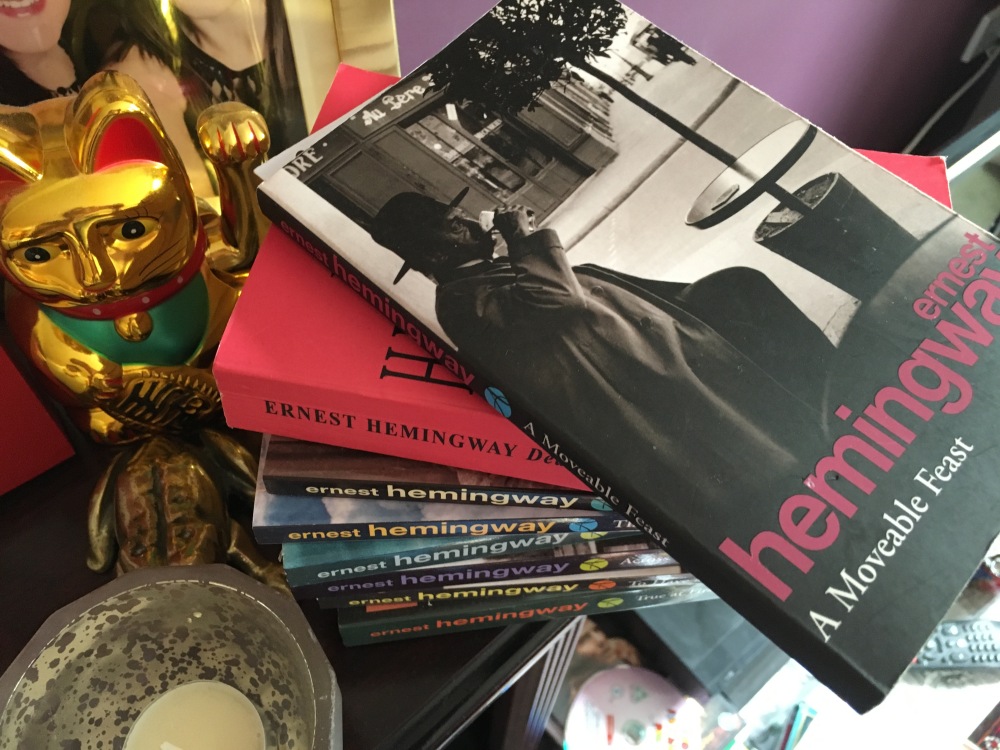

The idea that this titan of literature struggled with the expression of truth in a way that resonated with people, but used his own experience and training to bring the clarity and honesty of news writing to make his fictional works immortal, was intoxicating. I wanted to understand Hemingway, to follow, to absorb him. I wanted to catch the crumbs that fell from his table. So I began to hunt down his works. It’s now become a compulsion. I discovered a suntanned copy of Death in the Afternoon. I unearthed a cache of six of his volumes in an RSPCA shop thanks to an on the ball volunteer who saw me flicking through True At First Light. A Moveable Feast – the memoir of his years in Paris which most appealed to me and was the heaviest in the quotes included in “On Writing” – was ordered from the Book Depository.

With the books in my hands now I wonder – is this a road map to show me the way? Between these pages can I find guidance? Can I find a way to bring purpose, method and perhaps even the elusive endings to my efforts?

We shall see – but I think it might be a journey worth sharing. So I write this, and intend to write more, under a title which (as Hemingway suggested on many an occasion) with a title plundered from the Bible. Let us see what I can discover.

I really struggled with Hemingway when younger. I really disliked his portrayal of, and attitude towards, women, esp A Moveable Feast. So I’d be really interested to hear your thoughts ( have you read The Paris Wife, a fictional account of his first wife, Hadley, and their marriage and time in Oaris; an alternative view of A Moveable Feast). But, saying that, I do like the idea of his brevity of words and wonder if I should put my earlier prejudices aside and re-read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the perfect educational relationship is where you’re challenged by your teacher until the time comes for the pupil to make the challenge. I shall see what I think and report back!

LikeLiked by 1 person